As we enter the holiday season and month of thanks, I find myself reflecting on the many things I have to be thankful for in my life. But as I sit next to the fire writing this article, with my dog curled up next to me, there are few gifts I’m more thankful for than her. If your love of dogs runs deep, and since you’re reading this, I can only assume it does – then you understand. The profound joy, companionship, love, and devotion they impart illustrates a bond that was established thousands of years ago. But what was the catalyst that spurred such an undeniable connection and how has it been passed through thousands of canine generations and breeds?

Around 16,000 years ago, humans from Siberia crossed the Bering land bridge to settle North and South America. While the domesticated dog didn’t arrive for another 6,000 years, it was just in time to avoid the Bering land bridge’s collapse and make it onto the land mass that would later become the Americas.

In the 1960s and 1970s, archaeologists excavated two sites in western Illinois, where ancient hunter-gatherers collected shellfish from a nearby river and hunted deer in the dense forests surrounding the Great Lakes. Remarkably, these people also appear to have buried their dogs: One was found at a site known as Stilwell II, and four at a site called Koster, curled up in individual, grave like pits.

Radiocarbon analysis of the bones reveals that they are around 10,000 years old, making these canines the oldest dogs known in the Americas. It also makes these the oldest, singular dog burials anywhere in the world.

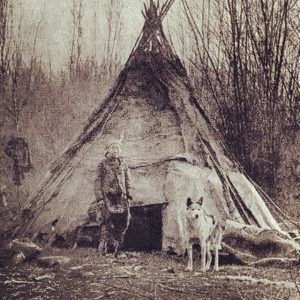

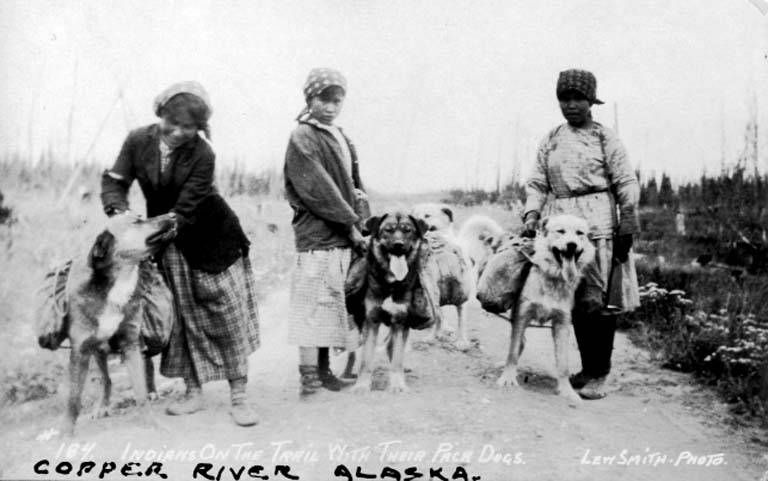

A testament that domesticated dogs have been important parts of native communities for centuries. Dogs played a pivotal role in helping humans hunt and transport goods, and they were sources of food and warmth through cold winters. Dogs were also incorporated in spiritual ceremonies for many tribes across what is now North America.

Different breeds of dogs were seen among different Native American communities. Genetically, the Indigenous dog is very similar to Siberian huskies, which highlights their history with human migration across the Bering land bridge from Siberia and Asia to modern day Alaska, which I mentioned earlier. Aside from the solo burial sites found in Illinois, many dog remains have been found buried alongside their humans since prehistoric times.

In Danger Cave, Utah, a small pup was found buried with a human in the caves, which symbolizes how close the relationships between humans and dogs were during this time. The dog had been wrapped in woven fabric and placed under the left arm of the deceased, as if they were simply asleep.

Other studies lead scientists to believe that some of these dogs came from domesticated North American Gray Wolves. Most modern studies have connected the lineage DNA similarities between the ancient Siberian dog breeds with the domesticated dogs common in indigenous communities. These dogs played a huge role in the survival and success of indigenous peoples during this time period.

Eventually, hunter-gatherers settled in small communities and began farming, which led these people to trade more frequently with different tribes. With trading came the birth of new breeds of dogs. These tribes would breed and train dogs specifically to fulfill the needs of their people. Some breeds of indigenous dogs were used for hunting, others helped with pulling farm equipment, and some were used as companions.

These dogs were significant in the communities of the indigenous Americans, but during the 15th century, many of these breeds began to slowly go extinct because they were being replaced by dogs of European descent when colonial settlers began colonizing indigenous people and their land. In bringing their own dog breeds to North America, they introduced diseases that the native, domesticated dogs were simply unequipped to fend off. Furthermore, many Europeans refused to let their European dogs mate with the indigenous dogs in order to keep the bloodline of their own dogs clean. However, there are a few modern dog breeds that share common DNA with their native ancestors, such as the Siberian Husky, Alaskan Malamute, and Greenland Dogs.

But the relationship between Native Americans and dogs has maintained a longstanding historical significance, and been both admired and revered. Many Native American cultures have the belief that a person is assigned an animal upon the time of birth. The animals are honored, as they bring teachings (known as “animal medicine”) throughout a person’s lifetime. Many indigenous peoples believe that animals have spirits and enter the human world to give their bodies to supply humans with food, fur and other materials. After their flesh is used the animals return home, put on new flesh and re-enter the human world whenever they choose.

Historically, a dog was seen as a sacred being that helped people, prior to the horse, by carrying wood, keeping watch of the camp, or towing the tipi. The ideas of the dog and its spiritual connections are complicated and often particular to different healers in the communities. Historians largely feel that once white settlers arrived with horses in the 1700s, dogs lost their place in Indian society, although they were still seen as an invaluable relative.

“In our culture, people traditionally don’t own animals the way other cultures have pets; the animals are left wild and may choose to go to a home to offer protection, companionship, or even to become a part of a community. People feed the dogs and care for them, but the dogs remain living outside and are free to be their own beings. This relationship differs from one where the human is the master or owner of an animal who is considered property. Instead, the dog and people provide service to one another in a mutual relationship of reciprocity and respect.”

– Lakota Tribe Members

The beauty of this belief and the intrinsic relationship the Lakota share with dogs, lies it the mutual respect and understanding that all living creatures have the right to independence and choice. New research shows there’s science behind this higher thinking. When canines stare into our eyes, they activate the same hormonal response that bonds us to human infants. The study—the first to show this hormonal bonding effect between humans and another species—may help explain how dogs became our companions thousands of years ago.

Brian Hare, an expert on canine cognition at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, says the discovery might lead to a better understanding of why service dogs are so helpful for people with autism and post-traumatic stress disorder. “A finding of this magnitude will need to be replicated because it potentially has such far-reaching implications.”

Canines seem to understand us in a way that no other animal does. Point at an object, for example, and a dog will look at where you’re pointing—an intuitive reading of our intentions that confounds our closest relatives: chimpanzees. People and dogs also look into each other’s eyes while interacting—a sign of understanding and affection that dogs’ closest relatives, wolves, interpret as hostility.

“I definitely think oxytocin was involved in domestication,” says Jessica Oliva, a Ph.D. student at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia.

Still, she says, “Mutual gazing doesn’t happen in a vacuum; most of these dogs probably associate the behavior with food and playing, both of which can also boost oxytocin levels. So, although we may view our dogs as our babies, they don’t necessarily view us as their mothers.”

At the very least, they view us as part of their pack, and that’s something very special to them…and to us.

Not long ago, I came across a beautiful Sioux legend that I think would be the perfect way to conclude this piece. I hope it touches your heart, and lives in your mind the way it has mine.

The Pact with Dog

When the world was created, First Man and First Woman struggled to stay alive and warm through the first winter, and First Dog struggled too. Deep into winter, First Dog gave birth to her pups. Each night, she huddled in the forest, longingly watching the fire First Man and First Woman built to keep warm. The first winter was so cold that First Dog dared not leave her pups to search for food, fearing her pups would freeze to death. Her belly shrank with hunger, and soon she had no milk. In the bitter wind, the smallest pup perished. First Dog felt her own life draining away as she struggled to care for the remaining pups. Desperate, she approached the fire to ask First Woman and First Man to share their food and fire’s warmth. She crept to the fire and spoke to First Woman, who was heavy with child.

“I am a mother,” said First Dog, “and soon you will be a mother too. I want my young ones to survive, so I ask you to make a pact.” First Woman and First Man listened. First Dog said, “I am about to die. Take my pups, raise them and call them Dog. They will be your guardians. They will alert you to danger, keep you warm, guard your camp, and even lay down their life to protect your life and the lives of your children. They will be companions to you and all your generations, never leaving your side. In return, you will share your food and the warmth of your fire. And you will treat my pups with love and kindness, and tend to them if they become ill, just as if they were born from you. You will have the loyalty of my young pups and all their offspring until the end of time.”

First Man and First Woman agreed. First Dog went to her pups and with the last of her strength, she brought each one to the fireside. First Dog licked her pups, and then walked away to die under the stars. Before she entered the night and returned to the creator, she turned and spoke once more to First Man.

“My children will honor this pact for all generations. But if Man breaks this pact and denies even one dog food, warmth, a kind word or merciful end, your generations will be plagued by war, hunger and disease, until the pact is honored again by all Mankind.”